macOS' Rapid Security Response: Designed into a Corner

With macOS 13.3.1 dropping a few weeks ago, some people have been wondering what happened to Apple’s featured “Rapid Security Response” system they showed off back at WWDC 2022? For some reason, Apple keeps shipping their usual slow, bulky security updates as opposed to the new small and “rapid” security updates.

Today we’ll look into how the Rapid Security Response was implemented and how Apple’s Engineers designed themselves into a corner with this new system.

- Note: This post will mention the “dyld shared cache” a few times. If you’re unsure what this is, I briefly explained it here

- Rapid Security Response: Cryptex comes to the Mac

- How Rapid Security Response Updates work

- Where Rapid Security Response falls short

- Is Rapid Security Response a failure?

Rapid Security Response: Cryptex comes to the Mac

With macOS Ventura, Apple changed a fair number of internals including how they handle their userspace binaries (namely Safari and the dyld shared caches). As I wrote last June, Apple switched from keeping the dylds on the APFS Snapshotted Root Volume to the system’s Preboot Volume with 2 clear goals:

- Implement more per-architecture differences

- Reduce space wasted by unused files (ex. x86_64h dyld on ARM64e Macs)

- Separate major userspace updates from root volume updates

- Reduce the amount of times APFS snapshot is messed with (RSRs only need a single reboot to apply)

With this move they adopted the Cryptex system previously seen with Apple’s Security Research Devices running iOS 14.

The Cryptex system can be seen as a pseudo-overlay to the operating system’s root volume, mounted under /System/Volumes/Preboot.

- Application calls to the root volume will instead be re-routed to the Cryptex paths (this is why apps that hard code library paths didn’t break in Ventura)

- Cryptex binaries should take precedence over root volume binaries

- Similar logic to Apple’s dyld system, on-disk binaries will always take precedence over ones fused in the dyld shared cache

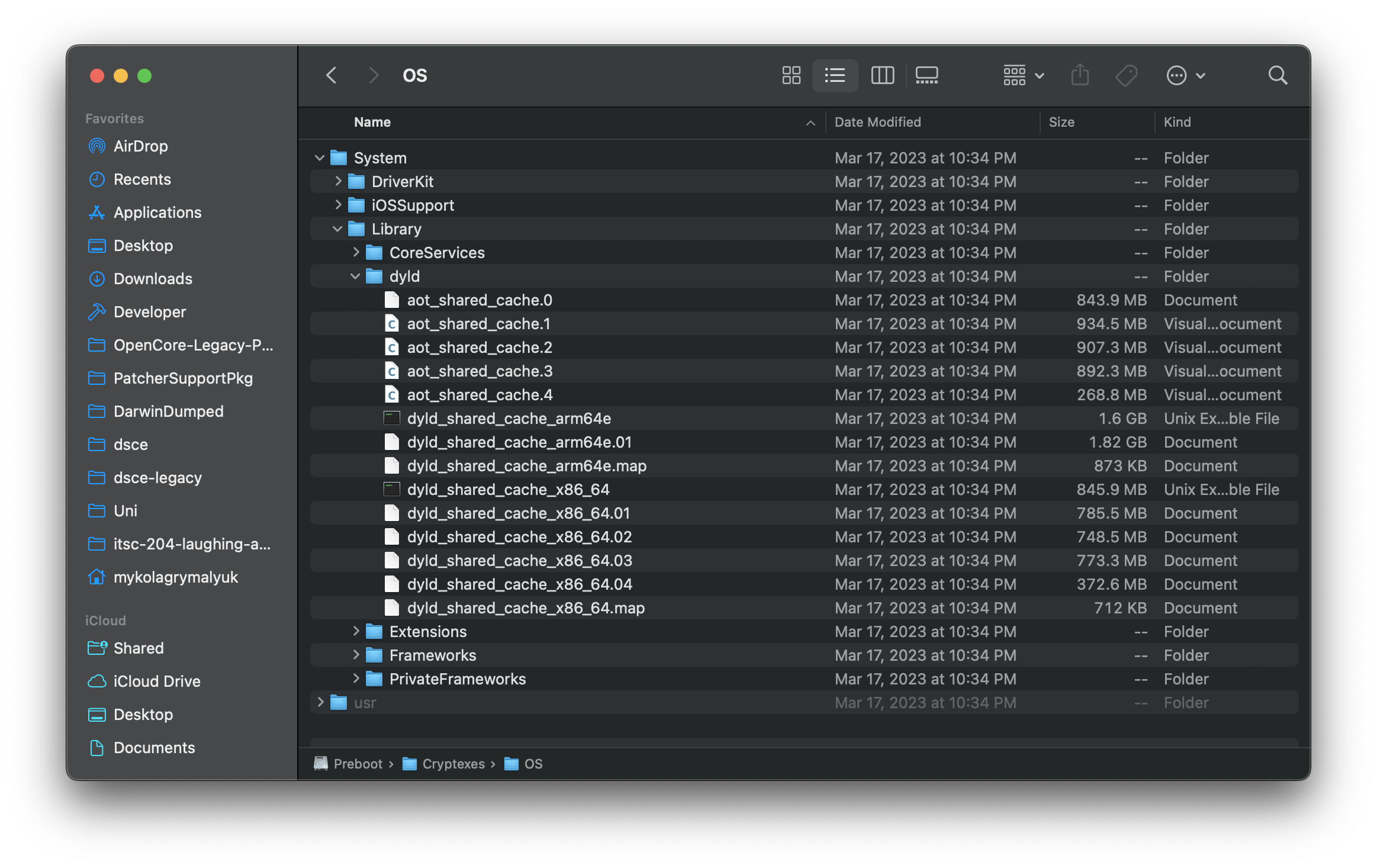

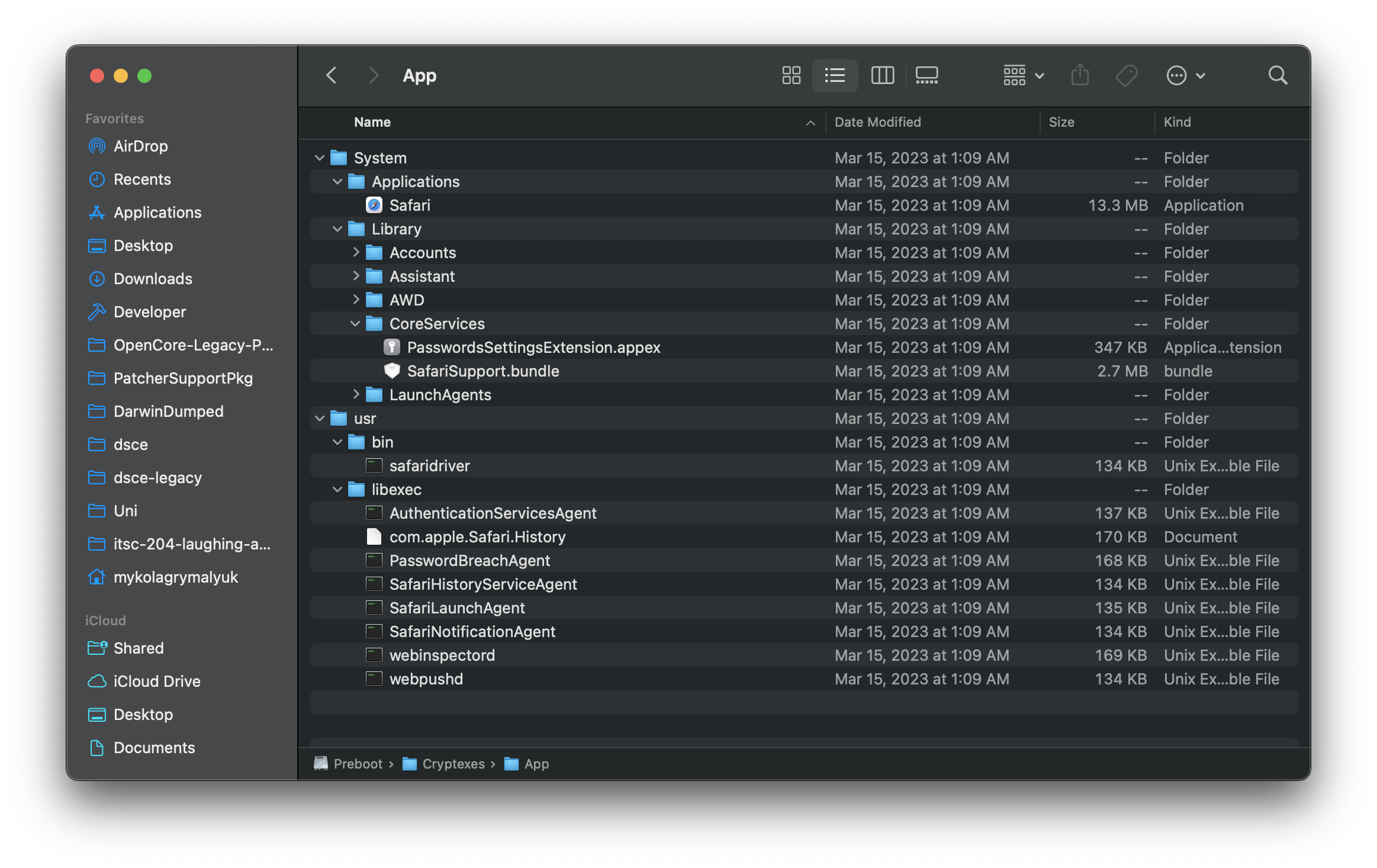

| OS mount (primarily dyld cache) | App mount (primarily Safari) |

|---|---|

|

|

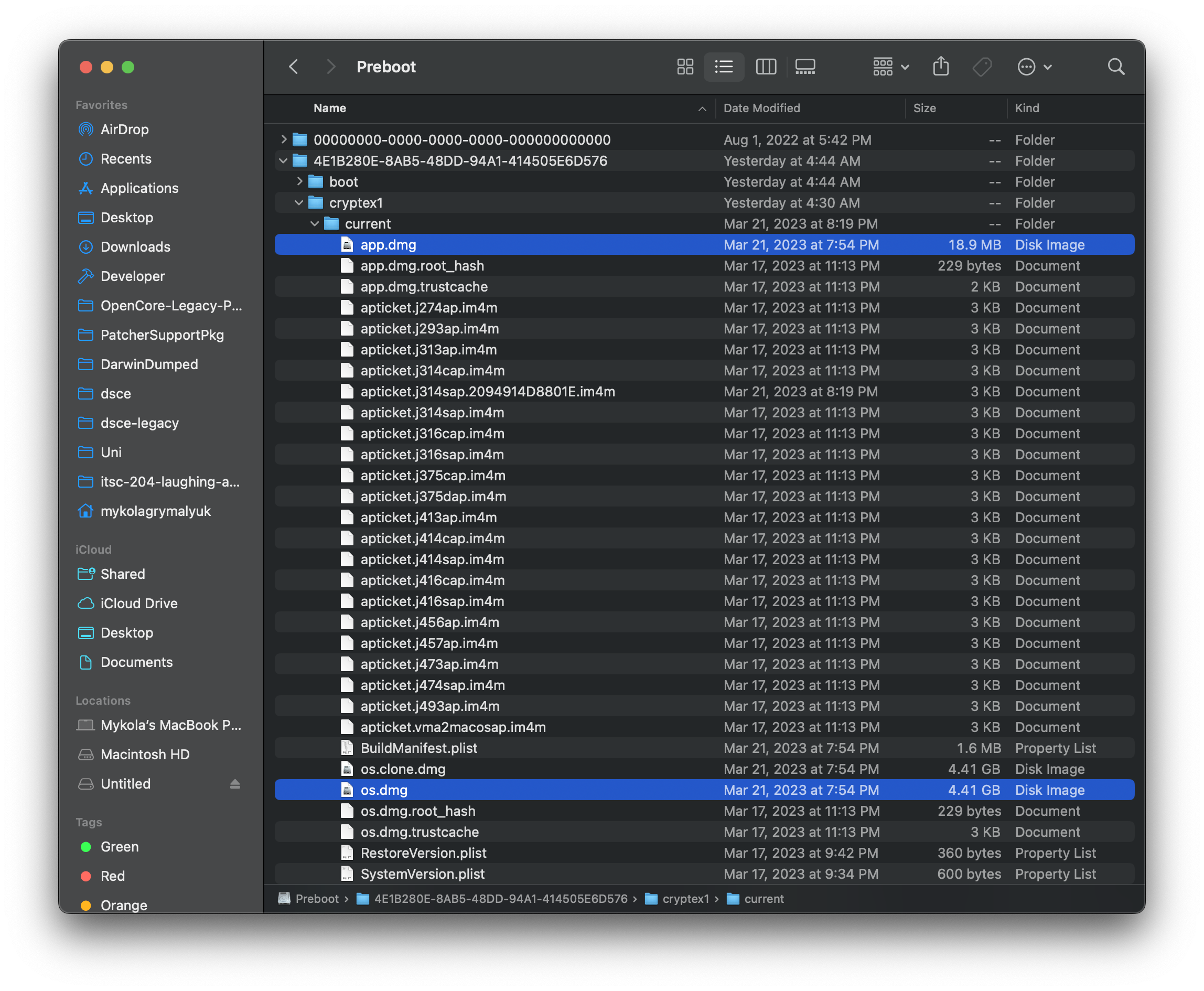

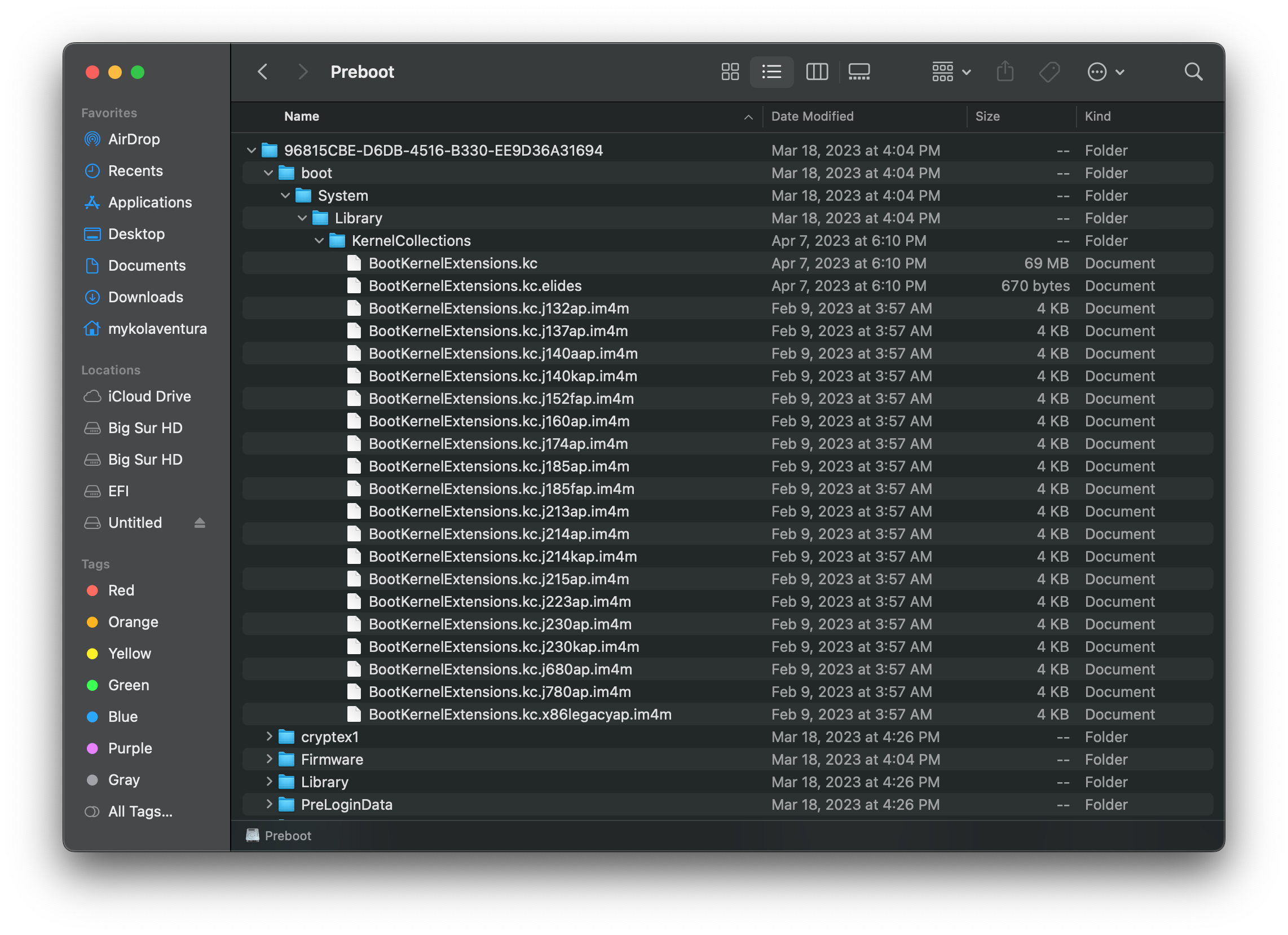

Regarding raw files, the Cryptex disk images can be found under /System/Volumes/Preboot/<UUID>/cryptex1/current:

How Rapid Security Response Updates work

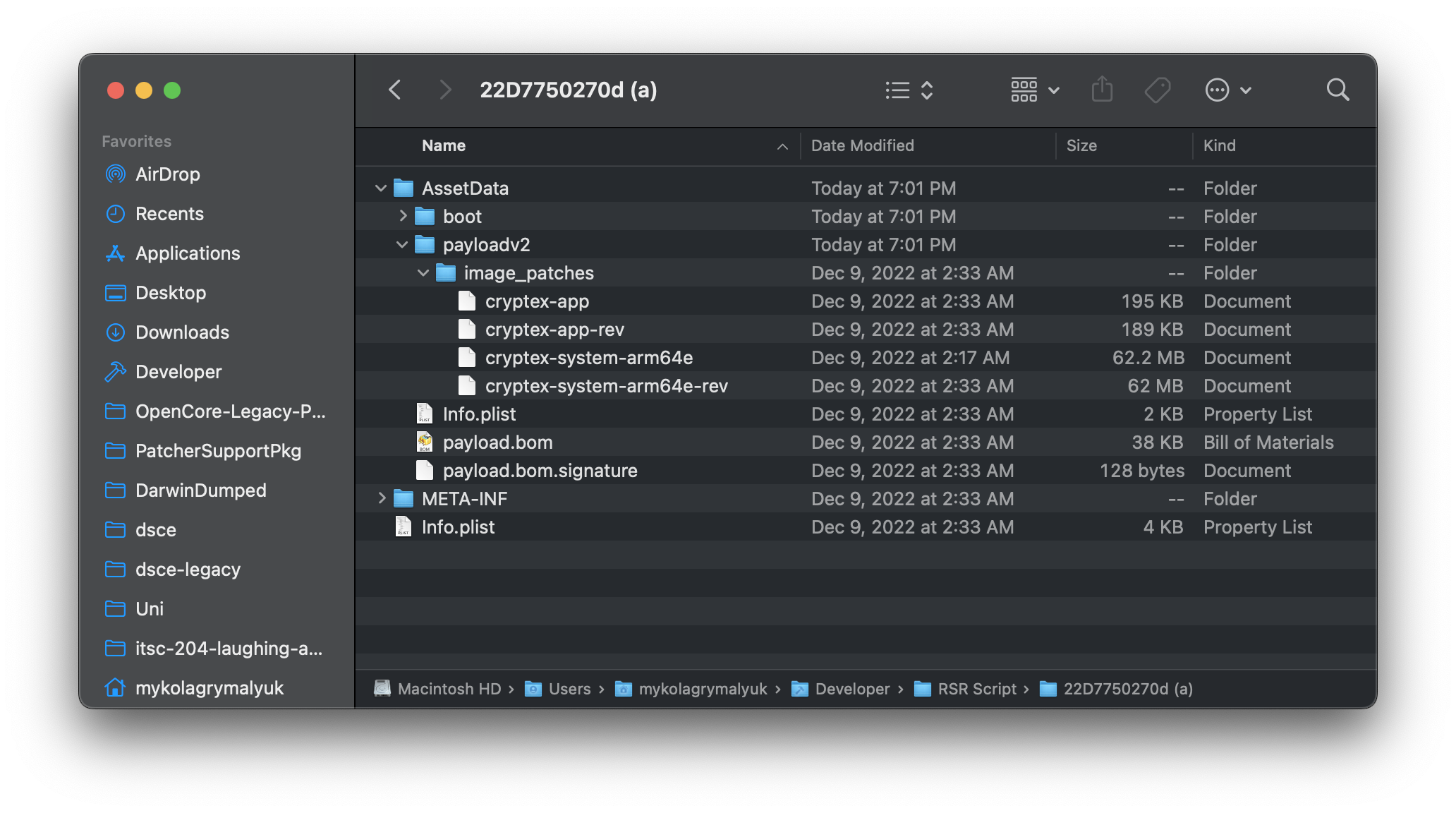

Now let’s take a peek at what’s inside a Rapid Security Response Update. For this, we’ll look at macOS 13.2 Beta 1 (22D5027d)’s RSR update, build 22D7750270d (a) (Apple Silicon variant).

When we download the update, we’ll see the following file structure:

For us, we specifically care about the following:

- cryptex-app

- cryptex-app-rev

- cryptex-system-arm64e

- cryptex-system-arm64e-rev

These files are of the RIDIFF10 file format, introduced along side macOS Ventura to explicitly handle Cryptex updates. This format is most similar to Apple’s BXDIFF50 used for OS updates with macOS Big Sur and newer.

- However we see something new here, the

-revfiles. These are used to revert the RSR update, which is needed as RSRs can only update the base OS- ie. older RSRs would need to be reverted before a newer RSR can be installed

- Also pay attention to file size, the RSR was only 120MB compared to a normal macOS update which is 3GB~. This is because RSRs are meant to only patch small portions of the OS, or even include stand-alone binaries to override the dyld version.

When a user applies an RSR update, they’re designated a letter at the end of their version (ex. (a), (b), etc)

To apply (or revert) these updates, macOS loads /usr/lib/libParallelCompression.dylib and requests RawImagePatch() to apply the image patches onto an existing Cryptex.

- Credit to DhinakG and ASentientBot for their research

class RawImagePatchArgs(ctypes.Structure):

_fields_ = [

("progressFunc", ctypes.c_void_p), # Optional.

("progressFuncKey", ctypes.c_void_p), # Optional. Can be anything you want, even NULL. Passed to progressFunc.

("inputFile", ctypes.c_char_p), # Optional. If not present, `*full replacement*`.

("outputFile", ctypes.c_char_p),

("patchFile", ctypes.c_char_p),

("isNotCryptexCache", ctypes.c_bool),

("threadCount", ctypes.c_uint32), # Limited to 2 threads max.

("verboseLevel", ctypes.c_uint32),

]

Where Rapid Security Response falls short

So why did both macOS 13.2.1 and 13.3.1 ship instead of using the new “fancy” Rapid Security Response? Well the answer is in what RSRs fail to handle: Kernel Space Updates

Something you may have noticed in our above conversation is a lack of security handling for updating macOS’s kernel and kernel extensions (kexts). The reason for this is that parts of Apple’s Kernel Cache system still reside on the APFS Snapshotted Root Volume.

A quick breakdown of Apple’s current Kernel Caching system introduced in macOS Big Sur, Kernel Collections:

- BootKernelExtensions.kc

- Houses macOS’ kernel (XNU) as well as essential kexts required to boot

- Resides on the Preboot Volume

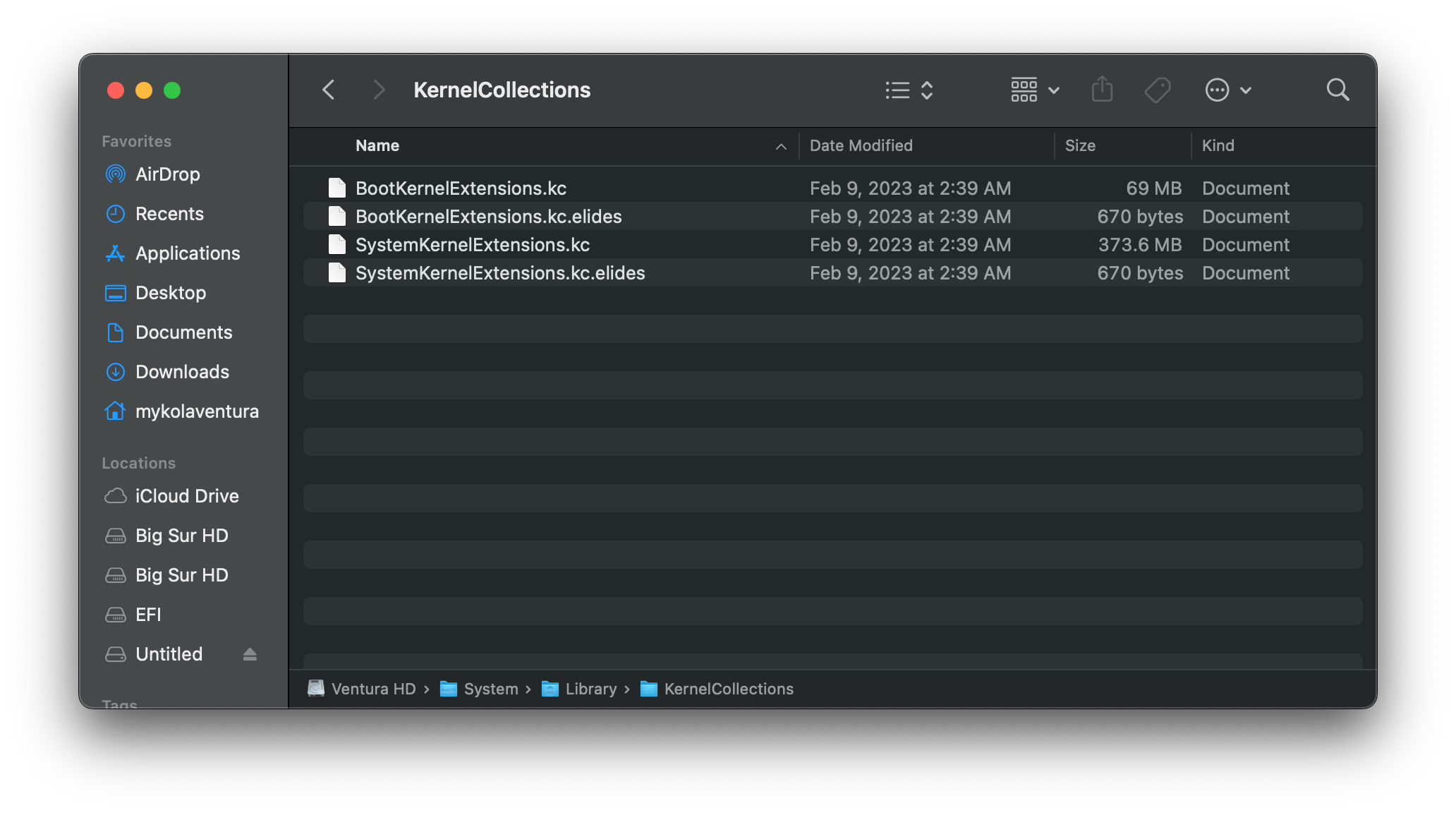

- SystemKernelExtensions.kc

- Houses any additional kexts including graphics and audio

- Resides on APFS Snapshotted Root Volume

- Unused on Apple Silicon installs

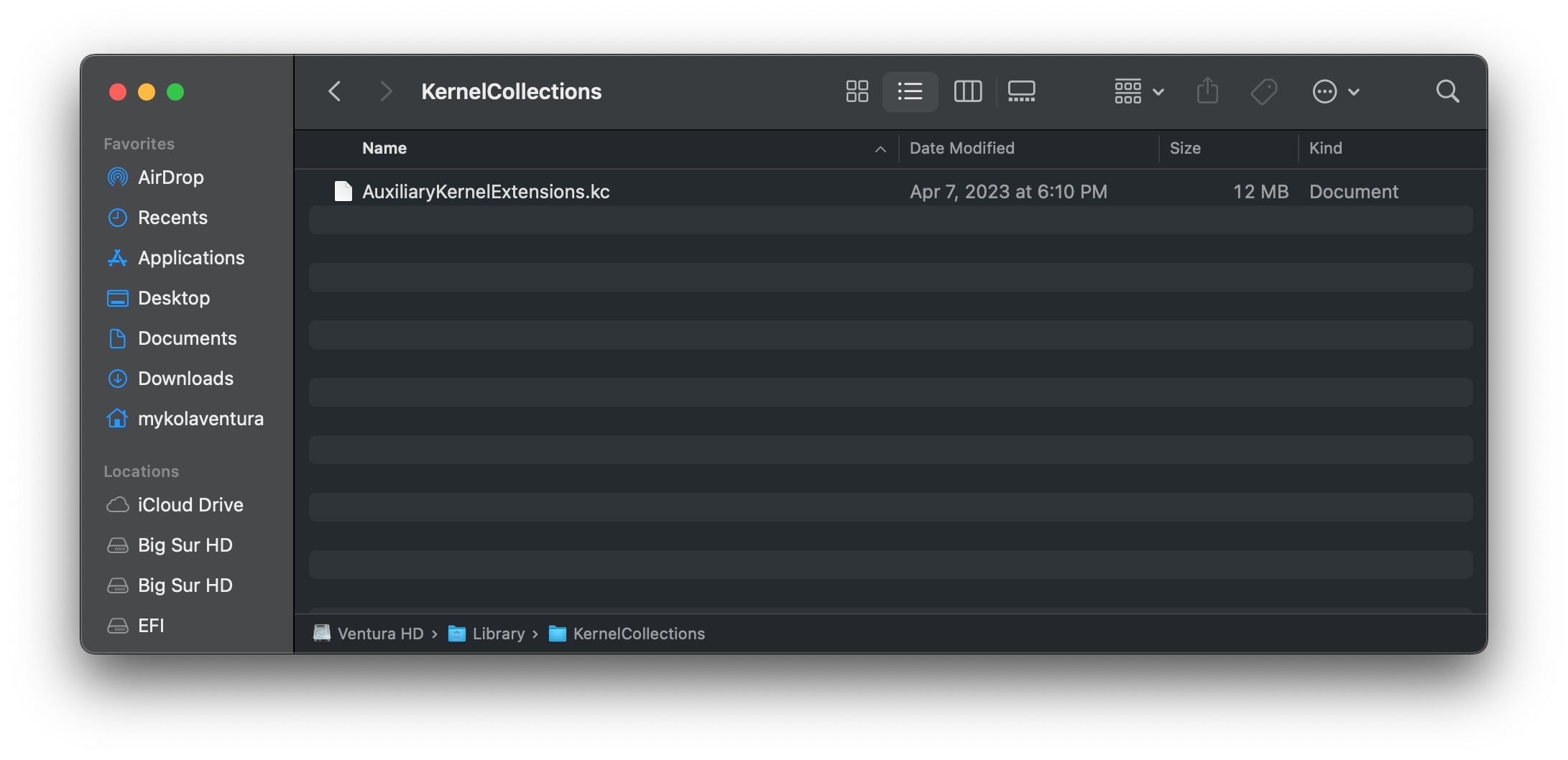

- AuxiliaryKernelExtensions.kc

- Houses 3rd party kexts, primarily installed by end-users

- Resides on the Data Volume

| Boot KC | System KC | Aux KC |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Because of how Apple architected the Kernel Collection system, all 3 caches are linked together and as such cannot be easily separated. Additionally, Apple killed the ability to hot-load kernel extensions from disk in Big Sur, forcing a rebuild of the Kernel Collection each time someone wants to either update the kernel or a kext.

- Now compared this to the dyld system, Apple can simply override the dyld binary with a stand-alone one allowing for both quick and small updates

Now let’s see what’s inside the security contents for macOS 13.3.1:

IOSurfaceAccelerator Impact: An app may be able to execute arbitrary code with kernel privileges. Apple is aware of a report that this issue may have been actively exploited.

And as we’d expect, the exploit is inside a kext! And thus, RSRs cannot be used to patch the exploit…

- Same issue applies in 13.2.1 as macOS’s kernel was updated: About the security content of macOS Ventura 13.2.1

Is Rapid Security Response a Failure?

When Apples Engineers designed this system, I genuinely believe they thought it would be the ideal way to handle security updates and be able to send them out quickly. However looking back at older OSes, I’m genuinely baffled by their decision to only prioritize userspace exploits and have no handling for kernel space.

If we look through macOS 12.6’s security updates, we see each one had both kernel and kernel extension exploits within them:

- 12.6.1: Exploits in Kernel and AMFI

- 12.6.2: Exploits in Kernel and IOHIDFamily

- 12.6.3: Exploits in Kernel and AMFI

- 12.6.4: Exploits in Kernel and AMFI

But perhaps this is an outlier, how about macOS Big Sur 11.6?

- 11.6.1: Kernel and Graphics

- 11.6.2: Kernel, IOUSBHostFamily and Graphics

- 11.6.3: Kernel and Graphics

- 11.6.4: No CVE published

- 11.6.5: Kernel and Graphics

- 11.6.6: Kernel and Graphics

- 11.6.7: No CVE published, likely just a Mail bug fix

- 11.6.8: Kernel, Filesystem, Wifi and Graphics

Clearly, there is an obvious trend here, kernel space is highly vulnerable and is constantly being updated.

While I do not know all the challenges internal faces when working with kernel security, clearly something needs to be done to address the slow rollout of security updates in macOS. However, due to the current kernel cache system, there is no easy way to integrate RSRs. Thus either a reworked or a brand-new kernel caching system needs to be implemented if Apple wants to continue with its initiative for rapid security updates.

As it stands, I don’t believe we’ll see Rapid Security Responses deployed in the wild when so many exploits are tied to kernel space and Apple’s slow pace to push updates. So now we wait and see whether macOS 13.4 (a) drops or only 13.4.1 ;p

Mini update: It seems we did get macOS 13.3.1 (a)! This doesn’t change my overall conclusion of the Rapid Security Response system, but it’s good to see it deployed in the public channel to combat exploits. This first RSR seems to be targeting WebKit.framework on the root volume (OS.dmg) while bumping Safari’s build on the data volume (App.dmg).

Now let’s play a bit of theory crafting: This blog post was released on April 18th, and 13.3.1 (a) was built on April 19th. I did hear through the grape vines that the engineers saw this post, perhaps one of them in Cupertino released this RSR build in spit ;p

Regardless I’m happy for the engineers to be able to finally release an RSR publicly, but now I’m curious if this was a one and done or whether Apple is committed to pushing more RSRs. Maybe WWDC2023 will have some interesting updates.